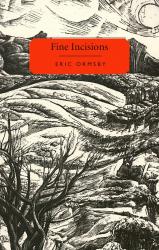

Fine Incisions is a collection of twenty-four gracious, intelligent and occasionally fractious essays, wide-ranging in their interests and rigorous in their analyses. Ormsby’s reverence for language is luminously clear as he examines his international travels, the work of James Merrill, the state of North American literary criticism and more in a series of essays as vivacious as they are provocative.

About the Book

‘A poem, I thought, is a physical object, as tactile as a statue. I began to consider poems in textual terms; there were shaggy surfaces, knobbly ones, mere veneers as sleek as glassine, but my favourites were those in which a complex and tensile music prevailed...’

Eric Ormsby, that gracious, intelligent and occasionally fractious poet, has produced another vigorous collection of essays to shake North American literary criticism from its lethargy. Opinionated and hilarious, Ormsby indulges his wide-ranging interests and discusses writers from Bob Dylan to S. D. Goitein, La Fontaine to Leo Tolstoy. Fine Incisions also draws connections between Ormsby’s literary criticism and his travel writing; as his essay ‘Shadow Language’ notes, the music of another language can seep pleasurably into a writer’s work (and, as Ormsby also notes, the lack of such linguistic overlap cheapens much of contemporary poetry!).

Although the topics vary widely, Ormsby’s viewpoint remains sharp and uncompromising, and his familiarity with North American, British and Arabic literary cultures informs each essay and leads to new and provocative reflection. Most of all, each essay is an expression of Ormsby’s own romance with language, and his devotion is clear in his adamant insistence on all writers’ very best.

Praise for Fine Incisions

‘... Ormsby is one of the two or three best English-language poets we [Canada] can fairly lay claim to. A fact that should be recognized someday.’

—Alex Good & Steven W. Beattie, The Afterword

‘A review like this one can only brush the surface of a collection so rich. And it’s simply impossible to praise it sufficiently. Its rare erudition and worldliness provide perfect ballast for the chiseled sentences of the essays, which flicker and snap with the energy of live wires. Ormsby borrows his title from a poem by Emily Dickinson, and does her honor in these essays that have the penetration of literal incisions, openings that cut deep into mystery, opening it to reveal all its shining interior.’

—Roger Sauls, Rover Arts

Culture is not something so easily broken down. Fine Incisions is a study of literature and culture from Eric Ormsby, as he discusses North American Literary criticism and hopes to challenge it to rise to the challenge, as he mixes in memoir with his own studies of culture, language, literature, and so much more. A poet by trade, Ormsby’s writing is sure to draw readers in, and his stories and discussions will resonate with any, critic and non-critic alike. Fine Incisions is a strong addition to any literary criticism collection, enthusiastically recommended.

—Mary Cowper, Midwest Book Review

Read an Excerpt

Butterfly on a Wheel: Bob Dylan

Whether writing on Tennyson, Eliot, Housman, Beckett, or many others, Christopher Ricks has always been a critic of exceptional learning and aplomb; that he has been generally given to a somewhat oblique, even eccentric angle of view -- embarrassment in Keats, the subtleties of punctuation in Geoffrey Hill -- has been to his credit, for while he is in one sense a traditional textual expert of rare authority (witness his editions of Tennyson and T. S. Eliot’s smuttier verses), he has also exhibited a delightful ability to surprise. His new book is no exception, less so in its erudition perhaps than in its surprises. Ricks, who recently completed a five-year term as the Oxford Professor of Poetry, has always been smitten with Bob Dylan; even in The Force of Poetry, his 1984 collection of essays, he included considerations of the singer as a poet rather than as a popular performer. It is clear now that his infatuation with the singer -- the word is not too strong -- has been no passing fancy but constitutes an all-consuming passion. With his new book, Ricks reminds us, on virtually every page, that the word ‘fan’ derives from ‘fanatic.’

All of Ricks’s impressive analytical strengths are on display in Dylan’s Visions of Sin. There is no song, no lyric, no mumbled comment from an interview with Bob Dylan, all cited here with excruciating exactitude, that does not elicit from this most acute of auditors some elaborate and, at times, almost comically inflated gloss. Shakespeare, Milton, Donne, Keats, Larkin, and many others are adduced to shore up his case. While Ricks’s learning and range of reference remain as impressive as always, the very scale of the enterprise overwhelms its subject. It is hard to think of any singer or composer, however brilliant or original, whose work could stand up to the claims Ricks makes for Dylan: Schubert would have quailed with dismay, Noel Coward would for once have been speechless. There is in truth something annihilating in Ricks’s advocacy of Dylan; as I read I found myself wondering at moments if this book did not represent a strenuous effort at self-exorcism, as though subjecting the slightest song and the most casual utterance to such drastic dissection might free the fan at last from his fandom.

As he makes clear in several statements, which Ricks quotes approvingly, Dylan has always been an instinctual, unreflective composer. He is wary, and rightly so, of excessive speculation on ‘the artistic process’. Many of his songs, among them the most famous, have come to him seemingly out of nowhere, and he doesn’t care to track them to their sources. Spontaneity, or at least the aura of spontaneity, is crucial to the effect of the best songs, as is a kind of rambling vivacity; and yet, in his extended analyses, Ricks freights Dylan’s lyrics with so many allusions and references and echoes that the songs seem to have been composed in a graduate seminar rather than on the fly. If Dylan ever reads Ricks’s book he may find himself so paralyzed by self-consciousness that he never picks up his guitar again.

Ricks’s case is this: Bob Dylan is not simply a consummate performer and a marvellous lyricist who revolutionized popular music in America over the last several decades, but a poet and indeed, not just any poet, but a great one, worthy to stand alongside the most illustrious in the language. To make his case Ricks must first establish that Dylan is a poet and that he sees himself as such. Ricks asks, ‘But is Dylan a poet? For him, no problem.’ Ricks then quotes from Dylan’s ‘I Shall Be Free’:

Yippee! I’m a poet and I know it

Hope I don’t blow it.

These immortal lines somehow fail to convince me. But Ricks persists:

The case for denying Dylan the title of poet could not summarily, if at all, be made good by any open-minded close attention to the words and his ways with them. The case would need to begin with his medium, or rather with the mixed-media nature of song, as of drama. On the page, a poem controls its timing there and then.

Ricks then ushers in, of all people, T. S. Eliot, who he says ‘showed great savvy in maintaining that ‘‘Verse, whatever else it may or may not be, is itself a system of punctuation; the usual marks of punctuation themselves are differently employed.’’ ’ Eliot’s quite suggestive comment is used, however, only to buttress Ricks’s next statement that ‘a song is a different system of punctuation again.’ Well, maybe, but what does this prove? Not much, as it turns out, for Ricks has inserted the Eliot citation only to lead into Bob Dylan’s use of the word ‘punctuate’ in an interview. The interviewer asks him, ‘It’s the sound that you want?’ And Dylan replies, ‘Yeah, it’s the sound and the words. Words don’t interfere with it. They--they--punctuate it. You know, they give it purpose [Pause].’ So besotted is Ricks with Dylan that he can remark about this diffident and unassuming reply, ‘this is itself dramatic punctuation, though perfectly colloquial’ and then add, parenthetically, ‘and Dylan went on to say ‘‘Chekhov is my favourite writer.’’ ’ Come again? Ricks appears not to have noticed Dylan’s rather revealing statement that ‘words don’t interfere’; he sees more significance in that ‘[Pause]’ about which he comments ‘the train of thought being that punctuation, a system of pointing, gives point.’ At such passages in the book -- and there are, alas, many -- even the best disposed reader cannot help wondering what exactly Professor Ricks has been smoking.

I for one am perfectly prepared to acknowledge that Bob Dylan is a poet and sometimes a fine one. Certainly many of his lyrics are superior to much of what passes for poetry nowadays in America; they are marked by strong and sometimes subtle rhythms, they rhyme wittily, they deal with themes of general import rather than mere coterie or private concerns, and, best of all, they are remembered by people who don’t usually read poetry or even care about it. His songs have always been suspiciously literary; that, together with what Philip Larkin, in a review which Ricks cites, called his ‘cawing, derisive voice,’ helps to account for their novelty and appeal. But his poems on the page and his poems as sung are not quite the same thing. I would argue that it is virtually impossible for anyone who has heard ‘Desolation Row’ or ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ or indeed any of the well-known songs to read them purely as poems. To read the words (for anyone, that is, of my and Professor Ricks’s generation) is to conjure up Dylan’s voice as well as the tunes and the accompaniment, and to do so irresistibly. And I feel sure that if a Dylan ‘poem’ were to be declaimed straight at a poetry reading anywhere, the audience would immediately begin humming the tune. Of course, this doesn’t mean that they aren’t poems, as Ricks claims, but rather that they demand a different kind of reading. Ricks knows this and tries mightily, often invoking particular performances or recordings, but the fundamental problem remains and it weakens his argument.

As Ricks also knows, to write a learned tome about Dylan’s lyrics without the music is as misleading as it would be to analyze his tunes without regard to the words. Pretentious as it must sound, each song, even the slightest, is after all a Gesamtkunstwerk, in which melody, lyrics, and backup combine to produce the final effect, and this is as true of Bob Dylan as it is of Johnny Mercer or Irving Berlin. Moreover, Ricks almost completely ignores the musical milieu and context out of which Dylan’s art developed and says hardly anything about, say, the Blues. Anyone who has ever heard Blind Willie Johnson singing ‘Dark Was the Night’ knows that Dylan (who would be the first to acknowledge his indebtedness) has no monopoly on a sense of sin or a raspy and compelling voice.

...

About the Author

Eric Ormsby’s poetry has appeared in most of the major journals in Canada, England and the U.S., including The New Yorker, Parnassus and The Oxford American. His first collection of poems, Bavarian Shrine and other poems (ECW Press, 1990), won the QSpell Award of 1991. In the following year he received an Ingram Merrill Foundation Award for ‘outstanding work as a poet’. His collection,Coastlines (ECW Press, 1992), was a finalist for the QSpell Award of that year. A sixth collection, Time’s Covenant,appeared in 2006 with Biblioasis. His work has been anthologized in The Norton Anthology of Poetry as well as inThe Norton Introduction to Literature.

Eric and his wife Irena currently live in London, England.

You Might Also Like

Buy in Print

To get this book in print, order from your favourite indie bookseller, or

buy online from our distributor, UTP »