What does it mean to think, to imagine, to create, to be? Why do we believe what we do? Is death an ontological state of being, or is it a grammar error? What exactly is poetry? The varied writings in Jeffery Donaldson’s Viaticum explore life’s most basic questions—and its biggest illusions—from the nature of language to the rhetorical potential of the afterlife.

About the Book

‘When does a thought become part of a poem and when does it become part of some other form of writing? ... You jot something down and watch to see how it leans.’

In Viaticum, Jeffery Donaldson presents selections from his notebooks that represent, as Wallace Stevens might say, ‘a readiness for first bells’. These proto-arguments and poetic seedlings—musings on the process of thought, the power of language, the passage of time and the promise of the afterlife—wait to see if ‘not yet’ might be ‘already something’. They offer glimpses inside the mind of a thoughtful poet, and provide readers with a spiritual conductor whose orchestral rehearsal culminates in no actual performance—‘only the sense that we are ready now’.

Read an Excerpt

From the Preface

Writing escapes me. Let me get that out of the way. I never know how to write. I don’t know how to begin writing and I don’t know how to keep writing once I’ve begun. I don’t understand momentum. I don’t understand how words go together; I don’t know how they come right, or how (and whether) I know it when they do. They are Scrabble games, our poems, our novels and essays. The little tray of letters and words and sounds and ideas and images: something gets spelled out, and it goes from there. It’s always your move.

I could leave well enough alone, but words escape me in the other sense. Mine is the prison warden’s peculiar laziness: I keep words locked up within, sit passively over them, keep them in their cells. What could they have done that was so awful? Occasionally I let them out in exercise yards that are no bigger than a notebook. They pace, they lie quietly in their narrow rooms. Most of the time they behave well enough. But come certain mornings, when I go in to check, I find empty spaces, a hole in a wall, a narrow tunnel leading out into the fields beyond. They won’t be kept away from where they want to be. They want to be about. I think, don’t worry I’ll find them, I’ll round them up and get them to march in line. But not before they have done some further mischief.

I am fascinated with openings, brilliant starters, brilliant non-starters. ‘Mrs Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.’ ‘April is the cruelest month.’ What? How do they know? A first musical phrase, a first brush on the canvas, a first word. There is not anything, then out of nowhere an inkling proposes itself. A window onto a world. Or rather, a window onto a world and the world itself that you see through that window. Both at once. Wallace Stevens got it right:

The way the earliest single light in the evening sky, in spring,

Creates a fresh universe out of nothingness by adding itself.

With an audacity that only newborns and children understand, it allows itself to be what it is, just to see what happens. There is a strange ambivalence in that first appearance: a certain unfolding in an uncertain direction.

All sorts of people keep notebooks. I know friends who have them and while I long to take a peek I know that their disinclination to think of them as works in themselves is admirable and appropriately modest. I think of notebooks the way Elizabeth Bishop thought of account books. She said, ‘Account books? They are dream books.’ It is the daily work of trying to ‘account’ for things, first salvos, sketches that you keep to yourself. Beginnings in a sense are provisions for a journey, at the very least because every journey has a beginning that quite actually provides for it. What journey might a whole bunch of beginnings provide for? I began to wonder about my own writing habits, how my notebooks seemed, as Bishop says about her account books, ‘honeycombed with zeros.’ Never quite the actual first number. But there they were, giving the appearance of adding themselves up.

What are they to become? When does a thought become part of a poem and when does it become part of some other form of writing? Is it grounded in images whose alliances will be more metaphoric and intuitive? Or does it tend towards an intelligible logic that wants to say something? How in the end are these even different? ‘The poet never lieth because he nothing affirmeth,’ writes Sir Philip Sidney. Says W. B. Yeats: ‘you can refute Hegel but you can’t refute the song of sixpence.’ When are my notes trying to become irrefutable poems and when are they sticking their necks out, so to speak, and making a claim? The stakes seem crucial to me, even though the form of the writing itself seems, at least at first (at second? at third?) strangely the same. You jot something down and watch to see how it leans.

Some of these pages have clearly decided which way they want to go, though for me they still hold within them phrases that might have pointed them in another direction, towards another reason for being. Many of them I think hang in the balance, extended reflections drifting away from some poetic kernel, not yet having reached their point of no return. They are ‘false starts,’ not because the start was untimely, but because they don’t go past starting. How to embody that special state of mind that Stevens called ‘a readiness for first bells’?

I love books of aphorisms. James Merrill writes in his poem ‘The Broken Home’: ‘I have thrown out yesterday’s milk / And opened a book of maxims.’ He is getting at that sense, in collections of verbal zingers, of wanting to discard the dross in one’s life and start again from first principles. It is a tradition that includes Pascal’s everlasting Pensées, but more recently the Romanian writer E. M. Cioran’s volumes of think pieces (Drawn and Quartered, Anathemas and Admirations). Here at home, we have George Murray’s witty adages in his two recent books Glimpses and Quick, and Stephen Heighton’s excellent rigours and workables in his Workbook. There may be something in the water these days, in the Zeitgeist, that favours hints and guesses. Murray thinks of his ‘quicks’ as being poems boiled down, a rarefication. I like that. I think of my ventures as more preliminary and undecided, sometimes too little and sometimes too big for their britches. But through them I like to think of how things come to be, how they end, and where they go when they do both.

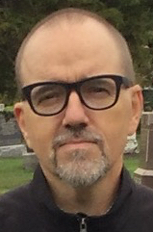

About the Author

Jeffery Donaldson is the author of five previous collections of poetry, most recently Slack Action (Porcupine’s Quill, 2011), which was shortlisted for the Hamilton Arts Council Literary Award for Poetry. Palilalia (McGill-Queen’s, 2008) was a finalist for the Canadian Author’s Association Award for Poetry. Donaldson has also written works of criticism on poetry and metaphor. He lives in Hamilton, Ontario, where he teaches poetry and American literature at McMaster University.

You Might Also Like

Buy in Print

To get this book in print, order from your favourite indie bookseller, or

buy online from our distributor, UTP »