In the Book of Hours, award-winning wood engraver George A. Walker creates a modern-day, secular devotional that captures in narrative imagery what is too devastating for words: the individual moments of innocence and routine life that ended with the onslaught of 9/11.

About the Book

The Book of Hours draws us back through time and into the intimate routines of daily life in the hours before the onslaught of 9/11. Here Walker expresses through images what is too horrific for words, and although the inhabitants of the Book of Hours can’t imagine the tragedy about to befall them, the reader must dread the slow, uneven countdown that weaves between the pages.

The Book of Hours juxtaposes the normalcy of telephones, cubicles and sex with the catastrophic consequences of 9/11, and Walker reveals the individual lives and stories affected by and hidden beneath global politics. Through a careful, reverential representation of all the minor tasks that make up a day, the Book of Hours pays homage to the small rituals that grant our lives some stability and meaning in the midst of horrific, incomprehensible events.

This is not only a remembrance of innocence lost but also a recollection of the historical activism and art genres that had such an important influence on today’s graphic novel. Walker contributes to the great woodcut tradition established by the likes of Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward and Otto Nückel, and shows the endless need to expose and question social injustice through art and narrative.

2011—ForeWord Magazine Book of the Year,

Shortlisted

Praise for Book of Hours

The idea that all art is a reflection of reality as interpreted and expressed by its creator or creators is a truism for many reasons. After all, even the most reactionary art bears the dim but discernable negative imprint of the very thing that it strives to destroy, ignore or reject.

Another, lesser known truth about art is that it generally works through an act of accretion. Basically, the steady accumulation and layering of information art generates interacts with its audience’s consciousness and willing suspension of disbelief. This, in turn, leads to a miraculous transformation of that most insubstantial of substances, our dreams, into reality -- even if it’s only for a moment, even if it’s only within the vaults of our imaginations.

Given that, how does an artist portray something that is, to its very core, a negation of the most cruel and final kind? How to capture artistically an event so horrific, so Apocalyptic, that quite literally it signaled the end of life as we knew it?

How do you make art about 9-11? Hell, how can you even make art after that terrible September morn?

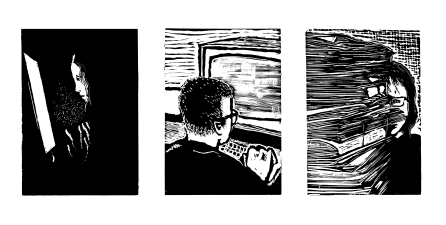

George A. Walker’s response is the Book of Hours, and it is eloquent, moving, and powerful. Over the course of 99 wood engravings, Walker tracks the mundane activities of a small cast as they go about their daily routines in the 24 hours before they meet their untimely ends when those two towers fell. And then, just when we’ve experienced enough to see ourselves in these poor, doomed shadows, they’re taken from us. Essentially, Walker uses the very nature of how we understand art to drive home the true cost of that awful day in a visceral, personal manner.

Thus we’re faced with not just the end of all these people’s lives, but also of our collective world -- real and imagined. It’s a realization that only heightens the bittersweet impact of Book of Hours.

Walker’s silent howl is an extended visual elegy delicately and boldly carved into the page by a sure, steady and skillful hand. It’s a dirge for a way of life and a mindset destroyed in the most public and profound of ways. Book of Hours deserves a place next to art spiegelman’s brilliantly faulted In the Shadow of No Towers, Rick Veitch’s sublimely surreal Can’t Get No, and other worthy titles which explore the meaning, impact, and ramifications of September 11th, 2001.

—Bill Baker, ForeWord Reviews

‘The woodcut artist George A. Walker’s print shop is a relic from another time. Housed in a converted garage behind his house in Toronto’s Leslieville neighbourhood, he moved it out of his basement after his wife complained about the smell. It is cramped but cozy, with everything required to release his artisanal books into the world....

‘It was here he hand-carved Book of Hours, his new wordless novel. Taking place on Sept. 10, 2001, Walker’s 99 wood engravings focus on those who worked in the Twin Towers -- from their homes to their offices, lives extraordinary only in their ordinariness. The book ends on Sept. 11 at 9:02 a.m., the minute the second plane hit....

‘Each image begins as a block of Canadian Maple. After inking on an illustration, he then uses an assortment of engraving tools to carve it out. He then places the block on his workhorse, a Vandercook SP15 proof press he bought years ago for $350, which he hand-cranks to produce each page. Time consuming, yes, but the process is part of the allure.

‘ ‘‘Why bother making woodcuts when I can make photocopies? Maybe put ink on a piece of paper and get a reproduction. What’s the difference? Why bother? Why bother to carve out of a piece of wood and make it such a long process? But it’s about the process, it’s about the journey, it’s about the immediacy, and it’s about that idea about the connection between the viewer and the actual element.’’ ’

—Mark Medley, The National Post

[Walker’s] curiosity and innovation, matched with a strong sense of social responsibility and common cause with his artistic forebears, led him to create his first wordless narrative entitled Book of Hours as a limited-edition portfolio of 99 painstakingly carved wood engravings examining the Sept. 11 attacks. It was released by Canadian publisher Porcupine’s Quill in 2010. Porcupine’s Quill is establishing itself as the prime Canadian centre for the publication and dissemination of wordless books, just as Montreal’s Drawn and Quarterly and Nova Scotia’s Conundrum Press and Invisible Publishing position themselves as the same for graphic novels. [...] The book art form Walker embraces gives him a wider vocabulary to tell readers about silence, the shapes of sounds, the elasticity of time and the nuances and shadings of mood - any phenomenon not easily visualized except in the unique nomenclature of a sequence of pictures.

—Tom Smart, "The great Canadian (graphic) novel", Telegraph-Journal

‘Walker reveals a society in which people follow their everyday routine, showing us small moments of normal life in the irretrievable time before terrorist attacks were considered possible on our own shores. The images are elegant, with a cumulative sense of active life, individuals captured in one moment of a full and personal existence. Rather than the story of one person, it accumulates the weight of narrative due to the reader’s foreknowledge of what is to come. Each page adds another life that is going to be forever changed.

‘This results in a striking book, with an overhanging sense of doom to the images of casual daily life, all those people just going about an ordinary day completely unaware of what was coming. Even in the form of fairly straightforward, uncluttered images, often of a single person who isn’t doing much at all -- sometimes gazing at a computer, sometimes lying in bed -- there is a sensation of alarm that grew stronger as I neared the end of the book. I didn’t want to see what I knew what about to happen. It was surprisingly affecting, powerful in its simplicity.’

—Melanie, The Indextrious Reader

‘It is a monument not just to an event but to the enduring power of traditional craft to capture experience.’

—Peter Mitham, Amphora

‘George Walker’s ‘‘Book of Hours’’, a wordless narrative brought to life by 99 intricate wood engravings, delivers with grace and a respectful sense of solemnity the stories of those who perished in the World Trade Centre attack ... It is the artist’s subtlety -- which resembles restraint -- that so insistently contrasts against other depictions and reports of recent terrorist activity.’

—Rachel Farquharson, ArtBarrage

‘Walker has summoned the retrospective tension that exists for many after greeting the morning of Sept. 11, 2001 without a specific regard to personal safety, terrorism, or the rupture of simple daily ritual.’

—Rachel Farquharson, Huffington Post

‘The delicacy and intelligence of George Walker’s print-making seems to have come to us from a bygone age. Fortunately, we have George with us now.’

—Neil Gaiman, author of The Sandman

‘I think the image of the young girl at the beginning ... could be the icon image of the 21st century.’

—Jim Horton

Read an Excerpt

From the Introduction

Having grown up on a rural farm town in Ohio, I attribute my love of books to the weekly visits from our county library’s bookmobile. My interest lay in the comic books and illustrated books published by Landmark Books and the Illustrated Junior Library, which were always tightly arranged on the shelves in the juvenile section of our stiflingly hot bookmobile. I grew up in a culture where the written word, not pictures, opened the door to knowledge. Although there was occasionally an illustration on the dust jacket of a book from the adult section, the pages inside were always restricted to text, and picture books were not for adults unless they were art-related or cartoons. After spending some time in the bookmobile, I soon concluded that reading books with pictures signified childishness or poor literacy.

By the time I entered high school, I obsessively perused stacks of books in my school library. Occasionally I came across books for adults with illustrations, like the outstanding volumes by the Limited Editions Club and the Heritage Press that commissioned famous artists to illustrate literary classics -- but these books were anomalies. I remained perplexed as to why there were no picture books for adults. Were they designated only for children? I had resigned myself to this unfortunate fate when, by unexpected chance, I discovered in a used book store a ‘novel in pictures,’ by the Belgian artist Frans Masereel, called Passionate Journey.

This narrative, told entirely in woodcuts, detailed the life of a young man living in the early twentieth century. Scenes of lovemaking and impetuous adventure, meant to snub the hypocritical culture around him, were depicted in simple black-and-white prints with dimensions of 3 ½ x 2 ¾ inches. Immediately I felt a strong affinity to Passionate Journey’s hero. Can you recall moments from your own life when you discovered a startling connection between your personal feelings and thoughts and another person’s, real or imagined? A connection that astonishingly illuminated your own sense of self?

I continued my search and quickly discovered additional wordless books by artists such as the American Lynd Ward, who, like Masereel, explored some highly-charged political and social themes in our Western culture. Although the majority of wordless books were mainly published in Europe and the United States during the early decades of the twentieth century, there continued to be a few distinct titles published in subsequent years.

As I uncovered these wordless books, my own culture started its infamous shift, in the late twentieth century, away from the written word and towards the use of images in communication. Our descriptions of and reactions to events began to align more closely with images, largely due to the increasing affordability of such technology as the television, personal computer and cell phone. Information delivered in a visual form gradually became the norm. Today there is even a language of pictograms, created as a universal language for instructions and directions, and which continues to grow in international use.

As our technology heralded the reign of the image, wordless books for adults appeared more frequently from the area of graphic novels, by recognized comic artists like Eric Drooker and Peter Kuper, and from the artist’s book -- a movement that began in the late twentieth century in which artistic expression was delivered in book format. Book artists specifically involved in creating wordless books were often printmakers committed to the revival of the production of books by hand, from cutting blocks to printing by hand on handmade paper in small editions. I soon made contact with many of the recognized artists in this field, including Babette Katz, Barbara Henry, Jules Remedios Faye, Christopher Stern, Rebecca Anne Blissell, Brendon Deacy, Olivier Deprez, and, more recently, George A. Walker.

I first encountered Walker in 1994 when I noticed his contribution in Crispin and Jan Elsted’s remarkable edition from Barbarian Press called Endgrain: Contemporary Wood Engraving in North America. I later discovered selections of Walker’s wood engravings in The Inverted Lineand Images from the Neocerebellum, and learned that he shared my passion for woodcut novels from his fascinating Introduction to Graphic Witness: Four Wordless Graphic Novels. In addition, he has shared his knowledge and techniques as a wood engraver and book artist in The Woodcut Artist’s Handbook: Techniques and Tools for Relief Printmaking, which is a thoughtful and invaluable resource for anyone interested in this type of printing.

As exciting and interesting as I found these books, I was immediately delighted when I read an advance copy of the Book of Hours: A Wordless Novel Told In 99 Wood Engravings. Up to that time, I had not seen an extended wordless story by Walker. I immediately recognized the title -- the Book of Hours -- as a tribute to Masereel, whose woodcut novel, Passionate Journey, had originally inspired my interest in wordless books and was, coincidentally, first titled My Book of Hours.

Walker has given a face to the men and women living in New York and working at the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center during the day leading up to the attacks on September 11, 2001. Walker captures various people and events in prints at various times during the day, involved in many of the activities that many of us experience in our own lives: driving to work, riding the subway, answering a phone, working on our computer, enjoying lunch with friends, walking home in the rain, watching television, or making love in our bedroom. By focusing on the people prior to the attacks and representing a commonality of routines and actions, Walker’s book ultimately binds us together as a community, a nation and a world. This thread of commonality and our emotional reaction, knowing the ensuing casualties, suffering, and loss, does not need any written explanation.

Walker presents a catastrophic moment in American history in his simple and skillful use of images and the Book of Hours generates a heartfelt surge of emotions without any need for words. With this noteworthy contribution, Walker joins a rich tradition of artists determined to express their ideas in pictures and to make their ideas available to everyone, regardless of language or level of literacy.

—David A. Beronä

About the Artist

George A. Walker (Canadian, b. 1960) is an award-winning wood engraver, book artist, teacher, author, and illustrator who has been creating artwork and books and publishing at his private press since 1984. Walker’s popular courses in book arts and printmaking at the OCAD University in Toronto, where he is Associate Professor, have been running continuously since 1985. For over twenty years Walker has exhibited his wood engravings and limited edition books internationally, often in conjunction with The Loving Society of Letterpress (and The Binders of Infinite Love) and the Canadian Bookbinders and Book Artists Guild (CBBAG). Among many book projects Walker has illustrated two hand-printed books written by author Neil Gaiman. Walker also is the illustrator of the first Canadian editions of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking-Glass books (Cheshire Cat Press). George A. Walker was elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Art for his contribution to the cultural area of Book Arts.

You Might Also Like

Buy in Print

To get this book in print, order from your favourite indie bookseller, or

buy online from our distributor, UTP »